How It Started

Around the pandemic, banks were flooded with deposits from multiple pathways – government transfers through the CARES Act, people accumulating savings by being quarantined in their homes for weeks/months, and very active capital markets (SPACs, IPOs, M&A activity and private market fundraising) in the months following the initial shutdowns. With the rapid influx of deposits, banks could not make loans at the same pace. So, instead, banks invested those funds in securities and, in many instances, longer term government securities that offered a yield premium to the deposit rate, which was effectively zero. That model worked well and fairly consistently until the Fed started aggressively raising interest rates beginning in March of last year and into 2023.

Spotlight

As a reminder, banks take in deposits (liabilities) and use those deposits to make loans and purchase securities (assets). And banks have two principal aims. The first is to earn a higher yield on the loans and securities it holds than it pays on its deposits. The second is to avoid realized losses on those loans and securities to avoid impairing its capital base.

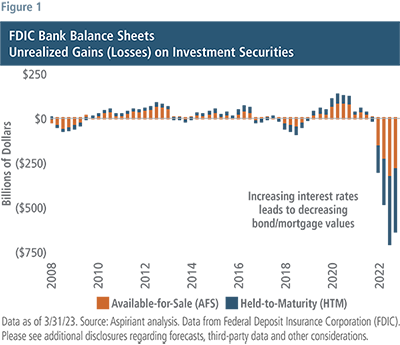

U.S. government securities are viewed as having virtually no credit risk, but they do have interest rate risk. As interest rates crept higher, the value of these investment securities declined. You can see that on the far right of Figure 1.

In 2022, unrealized gains quickly started turning to substantial unrealized losses. Without getting into technical accounting details on the classification of these losses, the important thing to know is that banks can manage the mark to market valuation adjustments to their securities portfolios – as long as deposits are stable. Once deposits flee, banks are effectively forced to sell or pledge assets to meet those demands, and these unrealized losses can become realized losses, triggering capital impairment and loss in confidence in the bank’s solvency or viability. In short, this is what occurred and caused the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank and First Republic and is pressuring the broader regional bank system.

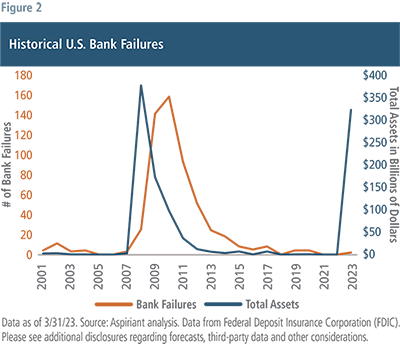

The FDIC’s list of problem banks has grown, not surprisingly, and with the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank, so too have bank failures, as seen in Figure 2. From the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) to today, there have been a few bank failures. Around the GFC, from 2008 to 2013, 80 banks failed, on average, per year with those banks holding $120 billion in total combined assets. As of March 2023, SVB and Signature Bank had total combined assets of $320 billion. In April, First Republic Bank had approximately $213 billion more.

While bank failures are occurring, it is important to note that the largest banks at the center of the crisis in 2008 appear to be in much stronger financial positions today. For a point of reference, the five largest banks account for roughly 50% of overall deposits and the top 10 largest banks hold about 65%. So, there have always been risks in the banking system – but, in our opinion, they are not systemic or widespread.

Credit Tightening

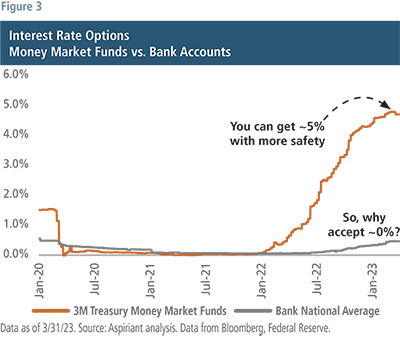

Initially, deposits were withdrawn as inflation started to bite and consumers had to rely on excess savings to make ends meet. During a more difficult fundraising environment, start-ups had to draw down cash to fund operations. More recently, as cash rates move closer to or above five percent, the gap between the yield on a money market fund and deposit rates widened out considerably as shown in Figure 3, inviting customers to move assets to more favorable non-bank vehicles or accounts. This has compounded the challenge for regional banks that have been losing deposits as their securities values decline.

Initially, deposits were withdrawn as inflation started to bite and consumers had to rely on excess savings to make ends meet. During a more difficult fundraising environment, start-ups had to draw down cash to fund operations. More recently, as cash rates move closer to or above five percent, the gap between the yield on a money market fund and deposit rates widened out considerably as shown in Figure 3, inviting customers to move assets to more favorable non-bank vehicles or accounts. This has compounded the challenge for regional banks that have been losing deposits as their securities values decline.

In fact, almost $600 billion in deposits have been withdrawn from banks. With lower deposits, the capacity to make loans lessens. With a higher cost of capital for banks, credit will be less available and likely more expensive, creating a further financial drag above and beyond the tightening affected by the Fed.

How It’s Going

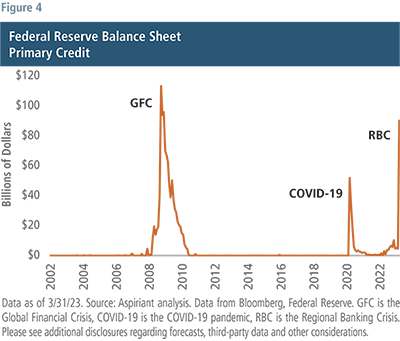

Around bank crises, the Fed typically steps in as a lender of last resort and provides needed liquidity to banks. For example, Figure 4 shows spikes in the Fed’s balance sheet or primary credit provided through the Fed’s discount window around the global financial crisis (GFC), later during the COVID pandemic, and now again with the regional bank crisis (RBC).

Initially, investors were focused on losses stemming from banks’ holdings of government securities. More recently, investors have also paid more attention to real estate loans, particularly commercial real estate loans which typically require more frequent refinancing. Sharply lower demand for office and retail space has led to lower real estate values, which in turn, has lenders less willing to refinance debt even at much higher rates.

Initially, investors were focused on losses stemming from banks’ holdings of government securities. More recently, investors have also paid more attention to real estate loans, particularly commercial real estate loans which typically require more frequent refinancing. Sharply lower demand for office and retail space has led to lower real estate values, which in turn, has lenders less willing to refinance debt even at much higher rates.

Unfortunately, the regional banks have much greater exposure to commercial real estate loans, representing about two thirds of their overall exposure. This may be the next looming risk to the regional banking system, particularly over the next two years, when several billion dollars of commercial mortgages come due. At this time, it remains very difficult to understand regional bank loss potential coming from their commercial real estate loan portfolios given the wide dispersion and variety of properties, sectors, locations, quality of underwriting and so on. Nevertheless, it certainly could continue to weigh on the outlook for regional banks and on the minds of investors.

Talk to us

Talk to us