Investment Strategy & Research (IS&R) Team’s Highlights

- Fed tightening cycles work on a lagged basis, usually over 21-27 months, and we are 15 months into this latest process.

- While a soft landing is still in the cards, we think the probability of a hard landing is more likely.

- Regardless of the Fed’s path, we’ve constructed our portfolios to both, withstand volatility and to take advantage of opportunities.

- The most speculative ends of the market sold off dramatically in 2022. We believe we have yet to feel the full effects of the most severe tightening in decades.

- We continue to hold high-quality bonds, risk-dampening alternatives, high-quality stocks at reasonable prices with tilts toward international and value equities.

Uncertainty is high, and we encourage you to stay focused on the long term. The Fed currently finds itself in a tough situation: attempting to quickly knock out excessive inflation while simultaneously avoiding catastrophic side effects that could result from its actions. How this all plays out will largely influence what happens in the financial markets going forward.

Spotlight

The Fed’s Task and Toolbox

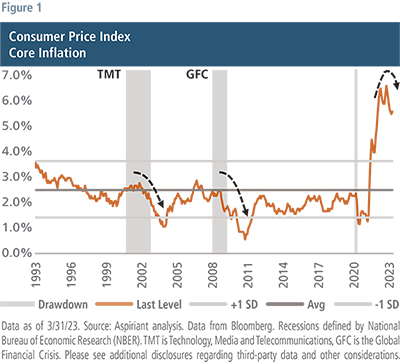

It’s good to recall that the Fed has a dual mandate. It attempts to set monetary policy in a way that ensures price stability, meaning low but stable price increases year over year. While its target level is 2%, inflation is currently around 5%. Simultaneously, the Fed attempts to support full employment. While there is no explicit target around that goal, most agree that the current level of unemployment at 3.5% is probably too tight of a labor market.

To pursue its dual mandate, the Fed uses a wide range of tools which typically fall under one of two approaches. When it wants to slow the economy and bring inflation back into balance, the Fed tightens monetary policy. To do so, it can increase short-term interest rates by increasing the Federal Funds Rate (the rate at which banks borrow from one another). The Fed also attempts to raise long-term interest rates by reducing (or tapering) the value of the securities it holds on its balance sheet (when bond prices go down, yields go up).

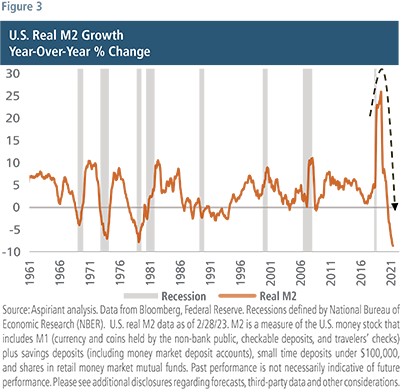

In March 2022, the Fed embarked on the steepest pace of interest rate increases in decades. The Fed’s rate hiking policy has been even more aggressive when you layer in the effects of quantitative tightening (QT). That means the Fed is reducing the size of its balance sheet, which saps financial liquidity from the system.

To knock out inflation, the first prong of the Fed’s dual mandate, it will have to raise interest rates and hold them high enough for long enough to reduce the demand for goods and services back closer to equilibrium. There are signs its policies are working, including cooling consumer and producer price increases, mixed commodities prices and cresting wages. But many effects are lagged and have yet to come through, including economic growth, housing costs, employment, corporate earnings and equity valuations. Throughout 2023 and 2024, we expect to begin seeing how these areas have been affected by rate hikes.

Unacceptable Levels of Inflation

The employment picture, the second prong of the Fed’s dual mandate, is at the crux of what many people refer to when they talk about what kind of “landing” will likely occur. If we experience a soft landing, we’d expect to see core inflation fall back soon toward 2% with no material weakening in growth, profits, employment or wages and no material cracks in housing, debt/credit and equities. If instead we experience a hard landing; we’d expect unemployment to balloon from 3.5% to at least about 5.5% – meaning approximately three million people or more would lose their jobs. While a soft landing is still in the cards, we think the probability of a hard landing is more likely.

Unacceptable Levels of Inflation

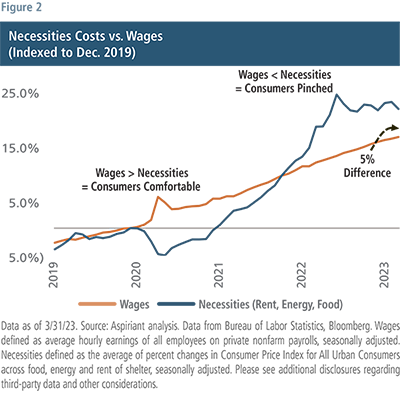

In 2020, inflation initially began increasing due to the rising prices of goods – when people were buying cars, appliances, etc. – when some were using their COVID-19 stimulus checks to do so. The prices of goods during that time were further exacerbated by supply chain disruptions, the War in Ukraine, China’s shutdown, etc. More recently, inflation drivers relate to wage pressures, especially in the services industry, which reflect the tight labor market. But, as wage pressures have begun to cool in recent months, we’re confident that year-over-year inflationary pressures will continue to ease in the months ahead.

The big question is, where will inflation ultimately settle? Given the overall strength in the economy, we don’t see inflation settling at or below the Fed’s target of 2% anytime soon unless the Fed keeps monetary policy tight (meaning rates high) for a while.

And that’s especially true for the most vulnerable among us, many of whom are forced to make tough choices to make ends meet. For example, as we previously discussed, many turned to using credit cards despite average rates nearing 20%, which is the highest level in over 50 years including the hyper-inflationary period of the 1970s and 1980s. Others reduced their household savings, which currently sits near the lowest level (4.6%) in decades. Even more gut-wrenching is the increasing number of people who have had to reduce or even deplete their retirement savings to maintain their lifestyles

Knocking Out Inflation

As interest rates increase, the economy slows because it becomes more expensive not only for buying necessities, but also for goods, cars, computers, services, dining and taking vacations. At the same time, higher interest rates dissuade speculation, especially on lottery ticket-type investments such as meme stocks, cryptocurrencies, NFTs, IPOs and SPACs. While the most speculative ends of the market sold off dramatically in 2022, we believe we have yet to feel the full effects of the most severe tightening in decades.

Borrowing rates across the board have skyrocketed. Over the past 25 years, we’ve only had rates this high on two other occasions – the Technology Media and Telecommunications (TMT) implosion in the early 2000s when the S&P 500 sold off 46%, as well as during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in the later 2000s, when the S&P 500 sold off 57%. Between 2016 and 2018, the Fed increased rates by just over 2%. Even that half-hearted effort to normalize policy caused the taper tantrum with a 23% selloff in the S&P 500, leading the Fed to quickly pivot the following year. So, it’s worthwhile to ask, “what damage will the current rate hiking cycle cause?”

We believe the answer depends on how high and for how long the Fed will hold interest rates. Currently, the market and the Fed have different responses to those questions. Investors expect the Fed to pause (stop increasing rates) soon and then pivot (begin reducing rates) later this year. However, Fed members themselves expect to keep rates a bit higher for a bit longer than that. If the Fed sticks to its plan (and not the market’s expectations), then investors, businesses and consumers will all experience tighter credit conditions. In that case, we’d expect to see a significant selloff in U.S. equities. So, how bad could it be? How long could it last? And when should we increase risk by adding more equities to portfolios?

Five Historical Rate Hiking Cycles

Although no one can precisely predict the future, we can better understand and anticipate how the future might unfold by studying similar environments. Let’s take a look at previous hiking cycles to attempt to frame what could be coming in the months and quarters ahead.

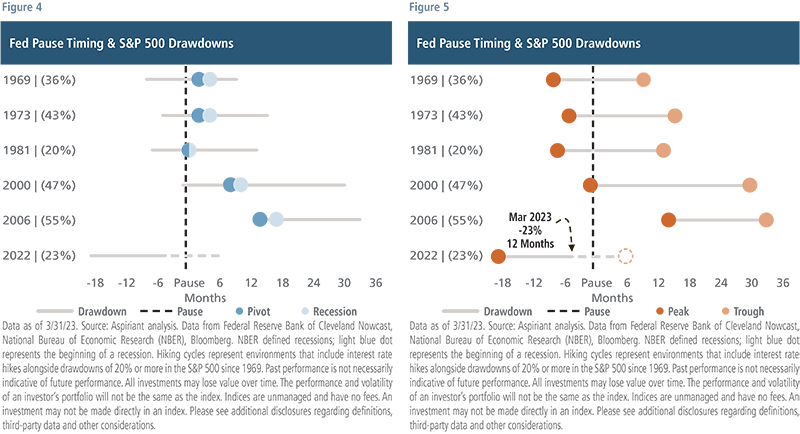

Figures 4 and 5 chronicle actual events that occurred during five previous rate-hiking cycles in which equities experienced a drawdown of at least 20%. The first rate-hiking period began in 1969, with the S&P 500 ultimately experiencing a drawdown of 36% (shown parenthetically). The second period began in 1973, with the S&P experiencing a drawdown of 43% and so on down the rows through 1981, 2000, 2006 and ending with 2022, which we believe is still ongoing.

Each period shows the number of months during which drawdowns occurred both before and after the Fed paused rate hikes. The date of the pause is indicated by the vertical, dashed black line. For example, the peak of the 1969 cycle occurred about eight months before the Fed paused and the trough occurred about nine months after the pause.

On average, across all five cycles, the S&P 500 experienced a decline of 40% over a 21-month period. For reference, as of March 2023, the S&P 500 experienced its max drawdown of 23% in September 2022. Since then, the market has recovered by about 13% and is currently down about 10%.

Therefore, from where we are today, if we assume the future of the current environment resembles the average of the previous five events, we would expect the S&P 500 to fall another 30% over the next nine months. That would take it down to a level in the low-3000s, with its trough representing a 40% total decline in the S&P 500, perhaps around the early part of next year.

Notably, across all five periods:

- The Fed did not pause until the Fed Funds Rate was above the level of Core CPI

- Pivots occurred a handful of months after the pauses

- Recessions began a couple of months after the pivot

- Market troughs occurred several months after the recessions began

- Equities gained an average of 80% over the three years following the troughs

So, without trying to get overly precise, we’re not at all surprised that the Fed has persisted thus far in raising rates closer to Core CPI. And we wouldn’t be surprised if it pauses soon, holds rates constant for a few to several months, then pivots around the time a recession begins, potentially toward the end of this year. The market trough could occur a handful of months thereafter. That’s precisely why we’re attempting to preserve as much capital as possible during downdrafts, giving us the opportunity to meaningfully compound client portfolios.

The Super Seven

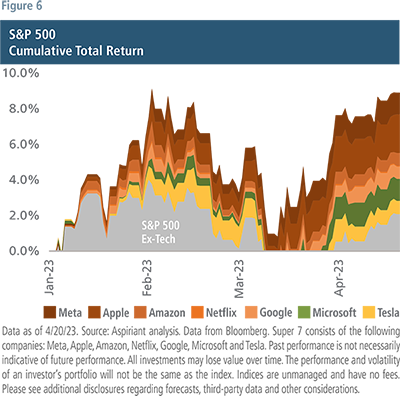

The S&P 500 advanced 7.5% during the first quarter of 2023, making U.S. equity appear strong, and masking many risks. Several anomalies that fueled the post-pandemic-market rally returned in the early months of the year, along with the January Effect. The most heavily shorted stocks and companies without profits advanced the most, and retail investors were active market participants once again. Notably, as was also the case in 2020 and 2021, market breadth was incredibly narrow.

The Super Seven — Meta (Facebook), Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Microsoft and Tesla —together have an aggregate market capitalization of $8.5 trillion dollars, account for about 25% of the S&P 500 index and were responsible for 75% of the S&P 500 gain in the first quarter of this year. Broadening out the lens a bit to isolate the 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500, those accounted for 90% of the first quarter advance. The other 490 stocks in the S&P 500 collectively returned 1% to 2%, depending on your point of reference. The Russell 2000 advanced less than 3%. So, for most listed stocks in the U.S., the quarter was not exceptional and mainly confined to movements in January.

More Risk is Supposed to Mean More Return

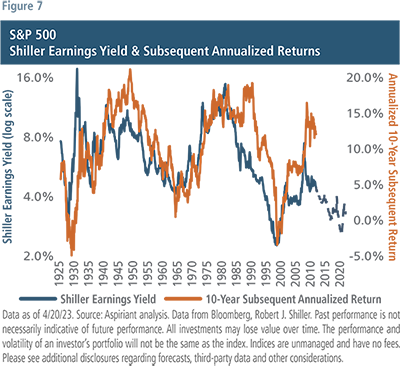

A straightforward approach to estimate long-term equity returns is to simply take the earnings yield or the inverse of the Shiller PE, shown as the blue line in Figure 7. This is the prior 10-year average earnings, inflation adjusted of the S&P 500, relative to the total market capitalization of the S&P 500. As you can see, the blue line closely tracks the orange line, the 10-year forward annualized return of the S&P 500, for much of the past 100 years or so. Today, the Shiller earnings yield is around 3%, suggesting a roughly 3% annualized return over the next 10 years for the S&P 500, or an amount barely above long-term inflation expectations and well below the double-digit annualized returns experienced over the past 10 years.

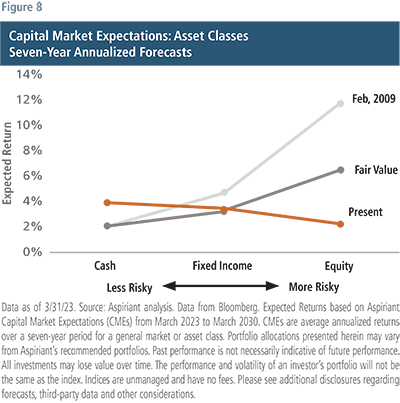

When we think about markets and economies being in balance, we consider three areas. First, is spending aligned with production? No, and that is why inflation is at multi-decade highs. Are incomes growing at the same rate as debt? Certainly not at the government level where U.S. debt to GDP has roughly doubled in the past 15 years. And finally, is there a risk premium or extra return available for investors for holding riskier assets? No, but with some exceptions.

In normal markets, bonds offer a return premium to cash and equities a return premium to bonds. For both the light and dark gray lines in Figure 8 that holds true. The difference being, the dark gray line reflects normal or fairly valued markets and the light gray line, with a steeper slope, represents a market with cheap valuations where the extra return is greater because of deep dislocations. Forward return estimates shown in light gray are measured in the depth of the global financial crisis in February of 2009. Today, we have the orange line in stark contrast to the other two lines. There seems to be no incentive to move out on the risk spectrum. Cash offers a return premium to bonds and bonds a return premium to equities. So, why hold equities at all?

Digging deeper, we find pockets of opportunity and specifically equities that do provide a return premium to bonds and cash. Our analysis indicates international value stocks offer an additional 4% to 6% return above the broad equity forecast of 2% shown in Figure 8. Over seven years, that extra return is expected to generate 30% to 50% in cumulative outperformance. And, importantly, these exposures allow us to create a more normal risk line and build more balanced portfolios.

Portfolio Positioning

We believe the current environment, with more uncertainty and dispersion across and within asset classes, is a more favorable environment for active management than that of the past 10 to 15 years. We continue to construct portfolios expected to be resilient to a range of outcomes.

Overall, we hold a bit less risk in our portfolios than our benchmarks, given risks are skewed to the downside. We maintain healthy allocations to fixed income and believe it will be a better ballast to portfolios than in 2022, as we near the probable end of the Fed tightening cycle. We still like diversifiers (assets that don’t move in parallel with traditional markets) as the return outlook for them has also improved, and they can provide some extra protection for a variety of unknowns.

Within equities, we are overweight international and value stocks, and defensive equities (stocks of companies with more durable and stable profits) remain a key holding in our portfolios. Where appropriate, private market allocations can also serve to enhance returns by taking advantage of market dislocations and further broadening overall portfolio diversification.

During times of shifting economic and market conditions, like the one we’re in, remaining invested and focused on long-term financial objectives is the best action investors can take.

Talk to us

Talk to us