Policy and Investment Outlook

For most of 2022, markets have acutely focused on inflation and the Federal Reserve’s reaction to this unruly data set. To date, the Federal Reserve has orchestrated the most significant tightening of monetary policy in 40 years. Short-term interest rates have jumped by roughly 4.5%, with more increases on the horizon. Given the lagged effects of higher interest rates on spending, and, in turn, economic growth, the consequences of these actions are now beginning to become apparent. A host of economic data, both here and abroad, confirm the slowdown, except for a rise in the unemployment rate, which has yet to materialize.

Nevertheless, we expect the narrative to shift to economic and corporate earnings growth in the months ahead. As that occurs, investors need to keenly assess recession probabilities and their implications on asset prices. Notably, corporate earnings decline by 20% to 25%, on average, in a recession, with wide variations around those central tendencies. Policy responses, or lack thereof, can and do affect the length and magnitude of a recession and their attendant effects on corporate earnings. For a number of reasons that we will discuss, the prospects of monetary and fiscal policy support, however, appear as narrow as any time since the early 1980s and create incremental risks for investors should a recession, in fact, occur.

While often thought of as two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth, a recession, as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research, is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy and lasting more than a few months. Broadly, recessions are triggered by a fall in aggregate spending and a downward spiral of less spending (since one person’s spending is another person’s income), job losses, increased savings, lower asset prices and additional cuts to spending. This self-reinforcing pattern requires an exogenous action, usually government policy, to interrupt the process and catalyze a recovery in aggregate demand. With that assistance, the economy can begin a revival and move the flywheel in the opposite direction – more spending leading to higher incomes, job gains, less savings, higher asset prices and even greater spending.

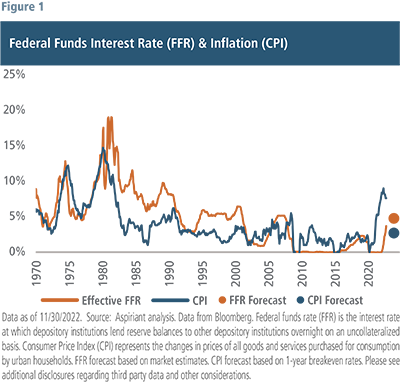

Historically, The Federal Reserve,  in order to suppress cascading price pressures, stops raising the Fed Funds Rate (FFR) when it exceeds the Consumer Price Index. Market pricing suggests the FFR will peak in early 2023 at or around 5%. With CPI rising by 7.1% on an annualized basis, as of its last reading in November, and the Fed’s expectation that inflation will remain above its target (of 2%) until 2024 or 2025, the Fed seems unlikely to lower rates over the next several months. Otherwise, it will risk the stop and start episodes of the 1970s when recurring bouts of high inflation were only cured by the draconian measures undertaken by Paul Volcker in the early 1980s, precedents Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly cited in his public remarks. Notwithstanding these limitations, any Fed easing from the estimated terminal (peak) interest rate of roughly 5%, if that occurs, will not have the palliative effect of prior accommodations. The extremely low interest rates in the post global financial crisis era, and in the months following the COVID-19 crisis prompted many households and corporations to lengthen the duration of their debts and fix their borrowing costs at rates well below the forecasted terminal interest rate. For example, roughly 85% of homeowners with a mortgage have an interest rate of 5% or less, a favorable spread of 1.5% or more to current levels. Accordingly, any drop in interest rates may provide less incentive to refinance/borrow/spend in the future and muddle the timing and force of a recovery.

in order to suppress cascading price pressures, stops raising the Fed Funds Rate (FFR) when it exceeds the Consumer Price Index. Market pricing suggests the FFR will peak in early 2023 at or around 5%. With CPI rising by 7.1% on an annualized basis, as of its last reading in November, and the Fed’s expectation that inflation will remain above its target (of 2%) until 2024 or 2025, the Fed seems unlikely to lower rates over the next several months. Otherwise, it will risk the stop and start episodes of the 1970s when recurring bouts of high inflation were only cured by the draconian measures undertaken by Paul Volcker in the early 1980s, precedents Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly cited in his public remarks. Notwithstanding these limitations, any Fed easing from the estimated terminal (peak) interest rate of roughly 5%, if that occurs, will not have the palliative effect of prior accommodations. The extremely low interest rates in the post global financial crisis era, and in the months following the COVID-19 crisis prompted many households and corporations to lengthen the duration of their debts and fix their borrowing costs at rates well below the forecasted terminal interest rate. For example, roughly 85% of homeowners with a mortgage have an interest rate of 5% or less, a favorable spread of 1.5% or more to current levels. Accordingly, any drop in interest rates may provide less incentive to refinance/borrow/spend in the future and muddle the timing and force of a recovery.

With monetary tools constrained, the burden to act, prodded by a quickening decline in economic conditions, then falls to Washington, D.C. However, the capacity of the U.S. government to expand spending without further disrupting financial markets and interest rates looks more limited due to years of significant deficit spending that have pushed debt to GDP levels to just above 120%. Despite years of low long-term interest rates, the U.S. government’s debt maturity averages around five years. As those debts come due, the U.S. government will incur higher debt service costs on new debt, adding incremental strain on its finances. In fiscal year 2022, interest costs ate up about almost $475 billion of the U.S. government budget. A sustained 2% to 3% rise in interest rates across the yield curve could boost annual interest costs, over time, to approximately $1 trillion or more! And rising debt service obligations might be further extended should the Federal Reserve (through quantitative tightening) and other institutions (e.g., banks and foreign investors) withdraw from or become less active buyers in the Treasury market.

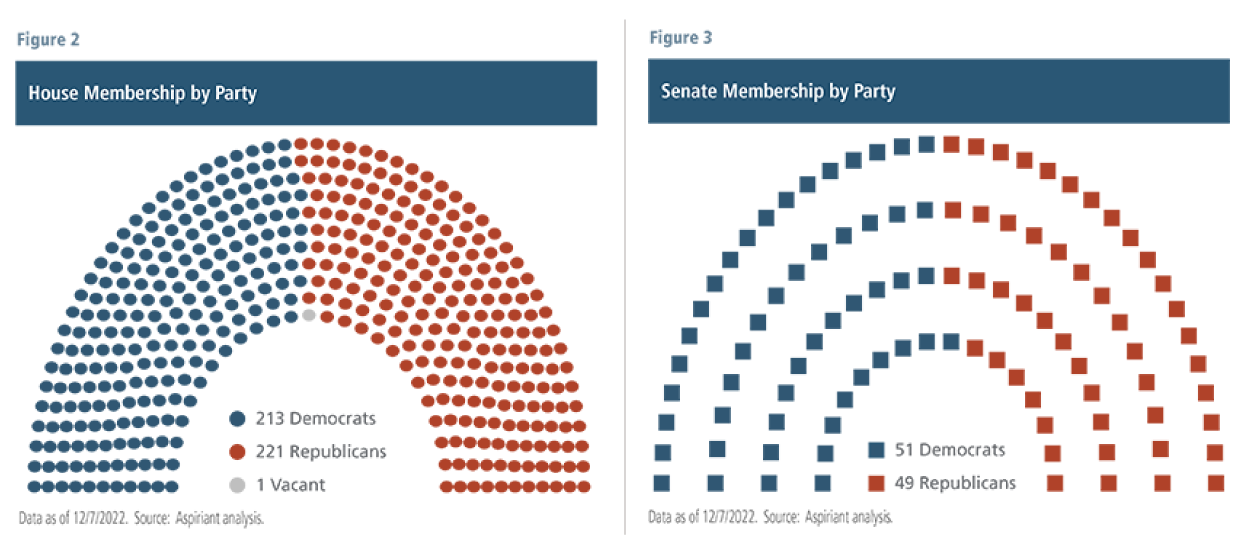

The federal government’s ability to stimulate is further checked by the results of the recently concluded mid-term elections and split government. Republicans, who will soon hold the majority in the House of Representatives, campaigned on promises to curb wasteful spending and lower the cost of living, two objectives that run counter to supporting significant stimulus. With fierce partisanship, wide policy differences and thin majorities in both chambers of Congress, the prospects of meaningful legislation seem low until after the 2024 elections. Admittedly, recent legislative victories on infrastructure, semiconductors and climate add some resiliency to the economy and perhaps can forestall the start of a recession. However, the collective annual spending from these programs of over $100 billion is insufficient, absent other programs, to jar a $25 trillion economy back on its axis of economic growth should it wobble and lurch into a recession.

As the year has unfolded, investors have consistently priced a swift return to historical inflation levels and ongoing economic and corporate earnings growth into asset prices. Changing interest expectations, rather than a fluctuating outlook for economic and corporate earnings has largely driven drawdowns in financial markets. While this soft-landing scenario is possible, it does not seem probable. Almost without exception, recessions follow periods of sharp monetary tightening. With policy support likely activated later and with less efficacy than usual, a growth stumble could become more embedded and harder to repair.

To better prepare for these rising uncertainties, investors, accordingly, should hold a portfolio calibrated to a range of outcomes, good and bad. In short, embrace diversification. In doing so, investors can stay more comfortably anchored to their long-term financial goals. And, importantly, be well positioned to capitalize on any dislocations should the environment prove more challenging than current market pricing suggests.

Talk to us

Talk to us