Part 1: Bridging the gap

Entering a bridgeway that’s under construction is a bad idea. Doing so assumes the overpass will be completed before motorists arrive. The road becomes more treacherous when the bridge needs to extend over a deepening and widening hole.

This unnecessary risk-taking is akin to what the brazen among us have been doing with their investments, consumption and health, threatening their own financial and physical well-being as well as those around them. By contrast, the sensible among us understand that there are no short cuts to long-term success. The allure of a seemingly faster, yet incomplete path presents more challenges than benefits. So, they wisely opt for an alternate, more certain route to safely arrive at their destinations.

Extending this analogy to the current economic landscape provides insights for investors, including how best to position portfolios in the years ahead. Since these are complicated but interrelated topics, our First Quarter Insight consists of two parts along with an accompanying supplement. In this Part I, we assess the overall size of the economic hole, which has grown considerably since the onset of the coronavirus. In Part II, we consider who might ultimately bear the burden of supporting the bridge to get us to the other side. The supplement describes some of the challenges and choices facing workers as they evaluate their role in reopening the economy by getting back to work.

What you’d have to believe

As the brazen barrel ahead toward the bridge, they are making many assumptions about the abutment of the structure:

Health & human

- Reliable testing, therapeutic treatments and effective vaccines will be broadly available

- Domestic and international healthcare system capacity will expand sufficiently

- People will feel comfortable interacting in close proximity with one another

- Civil liberties will take a back seat to comprehensive contact tracing to help prevent a second wave of infections

Business matters

- Employers will have the resources and confidence to invest capital and revert to pre-pandemic staffing levels

- Employees will be motivated and comfortable to go back to work

- Consumers will have both the means and desire to spend rather than save

Federal, state & local governments

- Governments, here and abroad, will make the right calls regarding the plan, procedures and pace for reopening economic activity.

- The U.S. Federal Reserve, as well as lawmakers, will sufficiently deploy additional monetary and fiscal stimulus, as needed

- Governments at all levels will successfully manage increasing levels of deficits and debts

Needless-to-say, a myriad of suboptimal outcomes could result from relying on such sanguine assumptions.

What else you’d have to believe

You’d also be making a number of assumptions related to the exposures in your investment portfolio. For example, in order to feel comfortable holding broad-based U.S. equities, you’d have to feel confident in the price and earnings levels of the S&P 500 index.

Prior to the onset of the coronavirus, the S&P 500 set its all-time high of about 3,390 on February 19. To us, U.S. equity valuations were stretched, an observation we have described as being priced to perfection. Well, imperfection occurred as the coronavirus hit: Economic activity collapsed as social-distancing measures were implemented broadly. Equities quickly followed suit with the S&P 500 falling in record speed to a more reasonable (but still not cheap) level of 2,240 on March 23. However, it didn’t take long for optimism to once again prevail with the index rebounding to 2,940, just 13% below the high, on April 29.

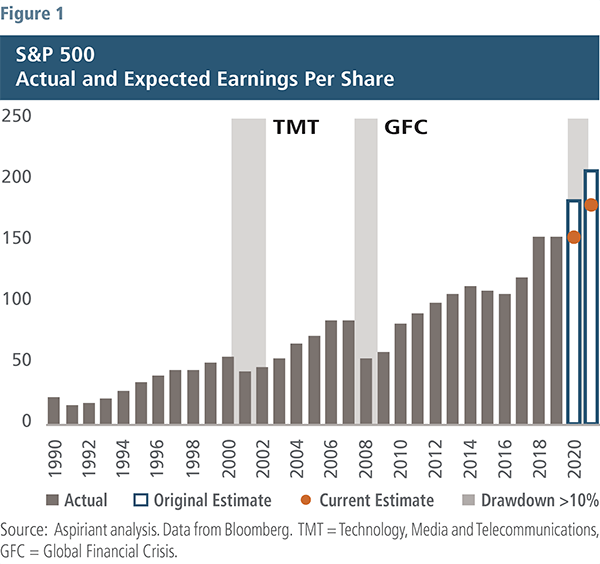

Wild as they may be, those price swings contain embedded assumptions about the forward earnings of the underlying companies. To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the actual and estimated consolidated earnings per share of the 500 companies in the S&P 500 index.1 Both the original and current consensus estimates represent the combined average of dozens of equity analysts’ earnings expectations for the underlying companies.

Wild as they may be, those price swings contain embedded assumptions about the forward earnings of the underlying companies. To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the actual and estimated consolidated earnings per share of the 500 companies in the S&P 500 index.1 Both the original and current consensus estimates represent the combined average of dozens of equity analysts’ earnings expectations for the underlying companies.

The original estimates (blue outlined bars) are as of the initial date for which estimates were available for 2020 and 2021. Typically, original estimates become available three years prior to the forecast year. So, the original consensus estimate for year-end 2020 was available at the beginning of 2018. The current estimates (orange dots) reflect the analysts’ most recent estimates as of March 30, 2020.

As shown, equity analysts were originally expecting earnings to climb — from $160 per share in 2019 to $180 in 2020 and $205 in 2021. Although they reduced their current estimates as the economic slowdown began, even those estimates may prove lofty as we move through the next year or two. In fact, we wouldn’t be surprised to see significant earnings misses, putting pressure on the price level of the S&P 500 as well as that portion of an investor’s portfolio.

So, why has the market whipsawed violently over the past several weeks, recovering more recently? Well, we believe the recent market action is indicative of a relief rally (a.k.a. bear market rally). These temporary market advances commonly occur during bear market declines. Professional investors welcome them as opportunities to de-risk portfolios by selling into the short-lived strength in the market.

How big is the hole?

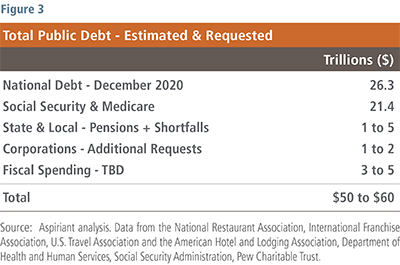

Having acknowledged the assumptions being made, the first step in assessing the danger ahead is to grasp the overall magnitude of the problem (size of the hole). So, rather than focus on the incremental debt associated with the current economic shock, we find it more useful to broaden our perspective — incorporating obligations we’ve all known about (in some cases for years) but have chosen to ignore. In so doing, we estimate that the country’s total public debt, starting with its headline national debt and then adding additional components typically excluded from the calculation.

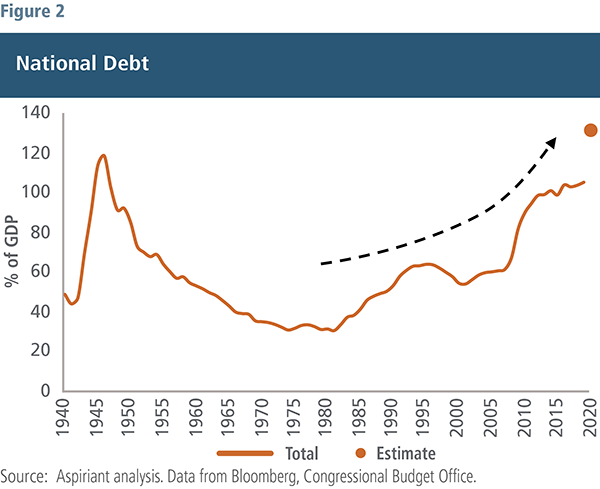

The orange line in Figure 2 plots the U.S. national debt as a percentage of GDP. As of December 2019, the United States’ official national debt was $22.6 trillion, representing 106% of the country’s GDP of $21.7 trillion in 2019. While full-year projections are being reassessed based on the coronavirus and resulting economic shock, we wouldn’t be surprised to see our national debt reach $26.3 trillion or more by December 2020. At the same time, we expect a decrease of roughly 6.8% in year-over-year GDP to $20.3 trillion in 2020. Based on those estimates, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio could balloon to 130% by year end, surpassing the previous peak set in 1946.

While our national debt ratio has exploded, it vastly understates the country’s estimated and requested obligations. That’s because some of the commitments, promises and favors falling to the federal government have not been recognized in the official figures. Those items relate to Social Security, Medicare, state and local governments, corporations, and other pending outlays.

While our national debt ratio has exploded, it vastly understates the country’s estimated and requested obligations. That’s because some of the commitments, promises and favors falling to the federal government have not been recognized in the official figures. Those items relate to Social Security, Medicare, state and local governments, corporations, and other pending outlays.

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of adding those missing pieces to the nation’s estimated year-end debt. As shown, we believe the country’s total public debt could be much closer to a staggering $50 trillion to $60 trillion.

We’re not trying to be overly precise with this analysis. Rather, we’re simply trying to create a rough estimate of the overall size of the problem in order to consider the options, if any, we have to adequately deal with them.

Social Security and Medicare

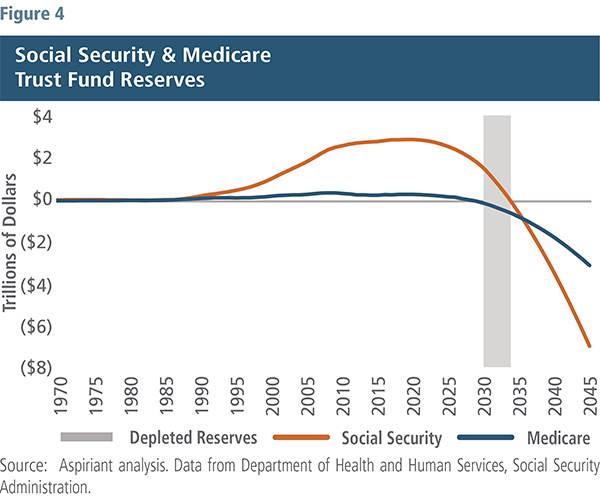

Social Security and Medicare represent critical components of the country’s social contract to provide basic financial and healthcare support to the most vulnerable among us. In recent years, disbursements to beneficiaries have exceeded inflows from payroll taxes. As a result, the trust funds for Social Security and Medicare estimate under-funded liabilities of $16.8 trillion and $4.6 trillion, respectively,2 as of December 2019. While we will likely have to make good on at least some portion of these promises, the massive shortfall of $21.4 trillion is excluded from the country’s headline national debt.

Furthermore, the day of reckoning is no longer in the distant future. Figure 4 plots the fund reserves, which are essentially the running excess cash balances for each trust. As shown, Social Security’s reserves are expected to be depleted by 2035, marking the first time in the past 40 years that benefits will exceed plan income. Projections for Medicare aren’t any better. In fact, that fund’s reserves are expected to turn negative five years earlier, in 2029.

Furthermore, the day of reckoning is no longer in the distant future. Figure 4 plots the fund reserves, which are essentially the running excess cash balances for each trust. As shown, Social Security’s reserves are expected to be depleted by 2035, marking the first time in the past 40 years that benefits will exceed plan income. Projections for Medicare aren’t any better. In fact, that fund’s reserves are expected to turn negative five years earlier, in 2029.

Once reserves are depleted, and assuming no changes to the plan parameters (retirement age, payroll taxes, etc.), the plans would have to reduce benefits to approximately 76% of their current levels. That would be a highly undesirable outcome since it would mean jeopardizing the health and financial well-being of millions of Americans.

While enormous, these estimates could severely underestimate the actual required funding. That’s because the baseline projections were determined before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and resulting economic turmoil. Massive job losses (discussed in Part II of our First Quarter Insight) create a significant reduction in personal wages and income, upon which the payroll taxes that fund these programs are based. So, depending on how long unemployment remains elevated, we could be staring at even larger funding gaps in the future.

CARES: Crossing the ravine?

In addition to the Fed’s vast financial support, The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, as amended, provides $2.8 trillion through various programs designed to support households and small businesses, among others, affected by the coronavirus. Those programs include:

- Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP) incentivizing small businesses to temporarily retain and compensate employees via forgivable loans

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) expanding state unemployment benefits by $600 per week through July 2020

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) extending unemployment compensation benefits by 13 weeks through December 2020

- Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL) providing low-interest loans of up to $2 million to small businesses

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) providing benefits to self-employed workers

- Economic Impact Payment (EIP) providing a one-time stimulus payment of up to $1,200 per person ($2,400 per couple), plus an additional $500 per dependent child under the age of 17

Collectively, these programs have provided relief. So, we commend Washington for the alacrity and bipartisanship to pass this law on March 27, just one week after the country’s record-setting initial jobless claims. However, we also question whether politicians, in their haste, created some unintended consequences across the programs.

State and local governments

Elsewhere, some estimates put the total underfunded state and local pension obligations at another $5 trillion, a growing problem we’ve known about for years. While the federal government isn’t required to backstop state or local shortfalls, these residents will either deal with the problems at the state level or seek political change at the national level. If the federal government can quickly support businesses of all sizes, then should it not also provide broad relief to state and local pensioners, many of whom are intimately involved with the day-to-day response to the crisis? So, we would not be surprised to see them vigorously solicit politicians who support the assistance before they accept reduced benefits. Regardless of who resolves the issues (federal, state or local taxpayers), the shortfall potentially adds to the country’s total public debt.

Moreover, up to this point, none of the federal support for the coronavirus has been allocated to state or local governments for general purposes. However, they are collectively calling for $750 billion in emergency relief to shore up their budget and avoid financial catastrophe in 2020.3 That’s because unlike the federal government, most state constitutions require balanced annual budgets.

Given the plunge in economic growth, states, counties and cities stand little chance of increasing revenue related to income, sales, property or excise/use taxes. Therefore, without a massive federal bailout or constitutional amendment, they will be forced to make severe cuts in other areas. No doubt, many will choose to furlough police officers, firefighters and schoolteachers, among other public employees. They will also very likely cancel or postpone construction projects that would have otherwise led to the creation of jobs.

To put this in perspective, as of 2019, state and local governments employed approximately 21 million people, representing more than 12% of the country’s overall workforce. So, headcount reductions would likely worsen and prolong the current economic downturn.

Additional federal outlays

Numerous companies, associations and lobbyists are also seeking hundreds of billions of dollars in federal assistance to cope with the devastating economic fallout from the coronavirus.4 Some of the largest requests include restaurants ($325 billion), franchises ($300 billion), hotels ($150 billion), airlines and aerospace ($110 billion combined), and mortgage companies ($100 billion). Aspects of the requests vary with respect to repayable loans, forgivable loans or direct transfers. The federal government certainly isn’t obligated to provide any such assistance to businesses, regardless of the terms. However, these groups collectively employ tens of millions of workers across the country. So, we have no doubt that the federal government will continue working with them to find viable solutions.

Looking ahead, we see numerous other possible spending initiatives that could be pursued in the coming months, including bills related to our national infrastructure, healthcare capacity, supply chain, alternative energies, and education or training. So, it is certainly plausible that trillions more will be added to our national debt as elected officials sponsor such programs. A crisis, particularly one of this magnitude, is simply too inviting for politicians to revive long-dormant spending plans under the guise of stimulus and economic recovery.

On the other side

Thus far, we are generally encouraged by efforts to contain the virus but believe we will struggle with its economic consequences for quite some time. It will be more like a marathon and less like a sprint. The virus may never be fully controlled or eradicated. In fact, it’s entirely possible that it simply becomes part of our “new normal,” and we’ll adapt and adjust accordingly, as we’ve done with plenty of other illnesses throughout time.

The immediacy of the health crisis will pass, hopefully soon. But life as we have known it may very well change. No doubt we will face new challenges, but we’re optimistic plenty of good will come out of it. For better or worse, the global pandemic has essentially pulled forward many of the trends that have been underway for years. We envision several positive changes in the future.

Our healthcare capacity will be vastly expanded. In the hardest hit areas, the coronavirus tested the limits of our medical professionals, hospital beds, respiratory ventilators and protective equipment. That should never happen again. For example, the U.S. currently has 2.8 available hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants. By comparison, South Korea has 12.3 beds per 1,000 inhabitants. We will attempt to close the gap. And, we’ll likely maintain massive stockpiles of ventilators, masks, shields and gowns to avoid the risk of future shortages and the toll it takes on our medical professionals. Finally, we will continue to develop consistently reliable and broadly available tests, tracing, treatments and vaccines for Covid-19. And, we’ll likely be better prepared to adapt such technologies when the next health pandemic occurs.

People will be more likely to save, building nest eggs better able to withstand another unforeseen downturn. A recent survey found more than 50% of respondents have tapped their emergency funds, while 63% are worried about running out of money.5 We doubt they’ll want to bear that burden again. In the future, people will more likely be concerned with having the essentials and less likely to care about discretionary items. Another survey found that 40% of those affected by the coronavirus have had to reduce spending on their most basic needs.6

Lots of small businesses won’t survive, while others will thrive. Virtually every company will change the way it does business. They will take visible steps to ensure employee and consumer safety, making sanitizer, gloves and other protective equipment available. Some businesses will serve customers differently, perhaps redesigning their restaurants, airplanes, hotels, stores and stadiums.

Some industries will shrink, such as travel, entertainment, energy and real estate, while others will flourish, including technology and healthcare. Working from home will become more common, providing a welcomed environmental benefit in the form of reduced pollution, congestion and noise. The drive toward globalization will be upended as companies instead prioritize the dependability of their supply chains. Corporate America will reduce operating and financial leverage and execute fewer share buybacks, thereby reducing structural risks as well as equity valuations.

Governments will offer additional public support and will likely spend, borrow and tax more to provide such programs. They will expand social safety nets, upgrade aging infrastructure, develop new ambitious projects, employ more people and increase individual and corporate taxes to help pay for it all. Countries that control their own currency, like the United States, will print money to partially fund the elevated spending. Governments will also address the widening levels of income and wealth inequality, which have only become more pronounced with the pandemic.

While some things will change, we have little doubt that we’ll continue forward as a strong, functioning and global society providing tangible benefits to the masses. In Part II, we further discuss the groups most likely to bear the burden of getting us to the other side.

1As discussed in our Third Quarter and Fourth Quarter 2018 Insights, the large change from 2017 to 2018, 2019 and 2020 reflects the one-time step up in earnings expectations related to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed in December 2017.

2Sources: Social Security Trust Fund and Medicare Trust Fund. Long-term (75-year) projections as of December 2019.

3Source: National Governors Association is calling for approximately $500 billion in state funding, while counties and mayors across the country have collectively called for roughly $250 billion more in emergency relief. Also, in a recent survey conducted by the National League of Cities and U.S. Conference of Mayors, nearly 90% of respondents said they expect to experience shortfalls in 2020.

4Source: National Restaurant Association, International Franchise Association, U.S. Travel Association, and the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

5Source: LendEDU.

6Source: Alexander Babbage.

Important Disclosures

Aspiriant is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which does not suggest a certain level of skill and training. Additional information regarding Aspiriant and its advisory practices can be obtained via the following link: https://aspiriant.com.

Investing in securities involves the risk of a partial or total loss of investment that an investor should be prepared to bear.

Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.

The views and opinion expressed herein are those of Aspiriant’s portfolio management team as of the date of this article and may change at any time without prior notification. Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.

Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. All investments can lose value. Indices are unmanaged and you cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of any index may be materially different than that of a model. The charts and illustrations shown are for information purposes only. All information contained herein was sourced from independent third-party sources we believe are reliable, but the accuracy of such information is not guaranteed by Aspirant. Any statistical information in this article was obtained from publicly available market data (such as but not limited to data published by Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates), internal research and regulatory filings.

The S&P 500 is a market-capitalization weighted index that includes the 500 most widely held companies chosen with respect to market size, liquidity and industry. Indices are unmanaged and you cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of any index may be materially different than that of a model.

Talk to us

Talk to us