Black ice: Dangerous conditions ahead

Black ice is a dangerous phenomenon often occurring on roadways during wet, winter weather. The thin, clear coating of icy glaze can be difficult to detect, especially for less experienced drivers. However, skilled motorists recognize the conditions and take advanced precautions to reduce risk. Such actions typically include driving defensively, especially when winding roads introduce additional uncertainty.

When aggressive motorists race ahead, disciplined drivers simply shake their heads and utter something like, “Idiots!” Prioritizing safety over speed, the truly skilled wouldn’t be enticed to keep pace with the reckless behavior.

As professional investors, we attempt to anticipate hard-to-detect conditions that could negatively impact our clients’ portfolios. With some exceptions, we believe the next market cycle will be characterized as a period of low overall expected returns. Although we’re not expecting a severe pullback, the risk of one occurring has increased as monetary tools have largely been exhausted and fiscal options appear remote given widening political divides. We recognize that a sharp turn in the road ahead, potentially triggered by a business-led slowdown or another catalyst, could cause a financial “spin out.” Therefore, remaining patient and cautious, given these precarious conditions, seems to us the most sensible course for managing assets.

Looking in the rear-view mirror

Like motorists who believe the road ahead will mirror the road behind, some investors believe the future will resemble the recent past. For example, looking backward, they might conclude that passively owning the market via a global balanced portfolio would be a sound decision going forward. We believe otherwise and think these investors risk being caught off guard, failing to notice how drastically conditions have changed and unwittingly endangering their capital over the next several years.

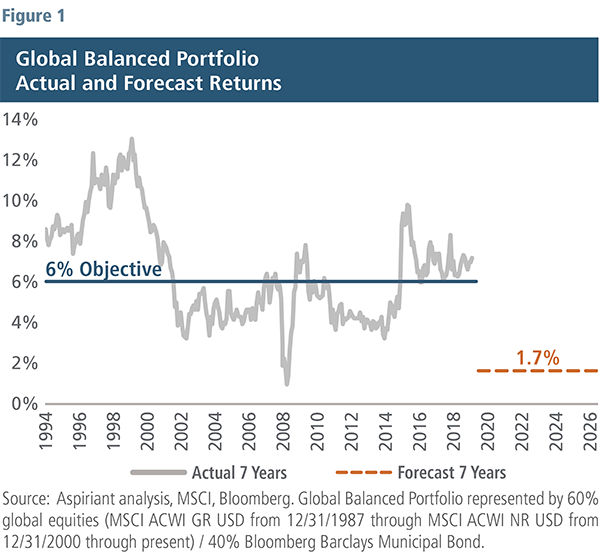

To illustrate the point, the gray line in Figure 1 represents the annualized returns generated by a global balanced portfolio over seven-year rolling periods dating back to 1994. About half the time, the portfolio either outperformed or underperformed an average annualized return of 6%.1 We think many investors would be satisfied earning that kind of return going forward. Unfortunately, past performance is not indicative of future results, which seems obvious given the significant difference between actual and average historical returns at any point in time.

So, to better understand and prepare for the future, we develop forward-looking seven-year annualized return forecasts across dozens of asset classes, which we call Capital Market Expectations (CMEs). Our current CME for a global balanced portfolio is represented by the orange dashed line, which suggests we’re entering a very low return environment. Indeed, over the next seven years, we expect the portfolio to average just 1.7%, annualized. Naturally, actual results will vary, either above or below, our assumed average. Importantly, our estimate is similar to those of three asset management firms whose financial forecasting skills we hold in high regard. So, we think we’re in good company and believe the low estimate is reasonable.

Needless-to-say, that low return would likely fall woefully short of most investors’ financial planning goals, perhaps forcing passive portfolio investors to make difficult decisions in the years ahead. Moreover, the estimate assumes things occurring outside the scope of our forecasting methodology that could either go right or wrong will offset each other. So, we assume these externalities won’t impact our forecasts, on average. However, a case could easily be made as to why downside risks will outweigh upside opportunities.

What got you here won’t get you there

Unlike the past several years, we believe the path to earning a reasonable return going forward is owning a portfolio that’s dramatically different than the market. That means pursuing an approach to weighting and rebalancing portfolio allocations that is distinctly different from a simplistic market capitalization-weighted approach.

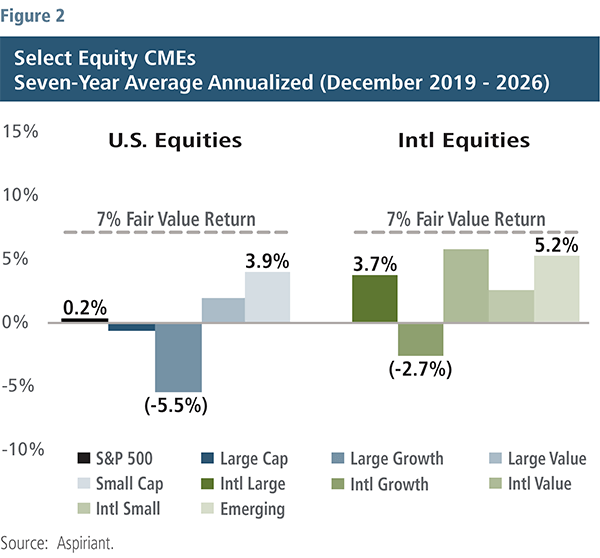

Our CMEs provide such an alternative. The forecasts act as guideposts indicating which asset classes should receive the highest or lowest weightings in a portfolio. For example, our forecasts for international large cap value stocks and emerging markets are more favorable than U.S. assets (Figure 2). Consequently, we want to hold the maximum allowable amount in those asset classes after considering other risk management considerations.

On the other hand, our forecasts for U.S. and international large cap growth stocks are actually negative and suggest these asset classes should lose money over the next seven years. Passively owning U.S. large cap growth stocks could result in a roughly 33% decline in that part of an investor’s portfolio!

To be clear, we’re not saying all large cap growth stocks around the world will become horrible investments. But, as we’ve discussed,2 we expect many of them to come under pressure. As a result, with the exception of high-quality companies, we believe in owning the bare minimum today.

Our CME process is dynamic, akin to an automobile’s GPS rerouting system. We routinely gather, compile and analyze information and then rebalance our portfolios as the investment landscape evolves. For example, our CMEs are constantly changing – some go up, while others go down. Moreover, some move quickly while others move more slowly.

Given the fluidity of these shifts, among other factors, our dynamic approach to portfolio management3 constantly assesses the positive and negative effects of rerouting our allocations across asset classes. Like a GPS, that doesn’t necessarily mean we dramatically or frequently alter our investment allocations. However, it does mean we’re constantly assessing ever-changing market conditions and evaluating the relative costs and benefits of making adjustments.

Flooding the market

How did we get to such low expected returns? Throughout the course of our careers, we have come to realize many investors perform little to no analysis prior to making investment decisions. This is referred to as price indiscriminate buying or selling, which tends to push stocks (especially growth stocks) to extremes during prolonged expansions or contractions.

Our concern is particularly acute for individual investors who tend to buy securities when the economy is strong. Anecdotally, their investing patterns tend to coincide with their consumption patterns because as the economy strengthens, personal incomes rise. That relationship not only provides more disposable income during expansions, it also affects a person’s ability to buy financial securities. The converse is true when the economy contracts and investors have less money to spend.

For example, Fidelity4 recently discovered 25% of its overall clients currently have too much stock exposure. It warned its client base about unnecessary risk-taking, along with the potential for serious losses exacerbated by a market meltdown. Even more strikingly, one-third of the firm’s baby boomers5 hold more than the firm’s recommended 70% in stocks for clients more than 10 years away from retirement. Moreover, one-tenth of that group is entirely in equities!

Imagine applying this behavior to the 72 million baby boomers across the country. What would happen to those investors in the event of a downturn? Who’s going to bail them out?

Making matters worse, we believe many individual investors’ decision-making parallels the way they shop for everyday goods or services — buy what’s cheap, popular or trending. As a result, we suspect individuals are overly exposed to low-cost funds (exchange traded funds), consumer companies (Big Tech) and trending securities (chasing performance). Because this type of investing requires virtually no analysis whatsoever, we believe it is a meaningful factor driving the market to have run well past fair value. Our incredibly low to negative forecasts for most U.S. equity asset classes fit this explanation.

Importantly, all stocks and bonds are affected by this kind buying and selling. Therefore, all market cap-weighted portfolios are susceptible to the ebbs and flows of “behavioral investing.” That’s because these portfolios automatically rebalance to the largest equity and bond issuances, usually on a monthly basis. As a result, they reallocate based on the momentum of the stock and, therefore, tend to be overweight growth stocks after long bull markets and underweight following bear markets.

Reaching a Fed end?

Business cycles and market cycles are interconnected.6 As an economy moves through a business cycle, the investment opportunities and accompanying risks in the financial markets change, often dramatically so. Ignoring where we are in these cycles risks becoming alarmingly unaware of the potential portfolio implications.

In contrast to behavioral tendencies, savvy investors understand that equities tend to perform better at the beginning of a market cycle (when growth is rising) while bonds usually perform better toward the end of a cycle (when growth is declining). Therefore, market cycles tend to lead business cycles by six to 12 months as skilled investors attempt to get out ahead of shifts in the economy.

It’s important to continually evaluate how business and market cycles work. While the level of valuations and margins are important, in and of themselves, they don’t necessarily portend an end to the cycles.

Traditionally, business cycles, and therefore market cycles, often come to an end as an extended period of growth leads to increasing prices for consumers (goods and services) and businesses (labor and resources). Anticipating the risks of these inflationary pressures, central banks respond by increasing the prevailing level of interest rates. Higher borrowing rates lead to a contraction in credit and lower consumption or spending. And, since one person’s spending is another person’s income, someone else has less to spend, which further reduces more consumption and so on. Eventually, the economy slows as the unwinding plays out.

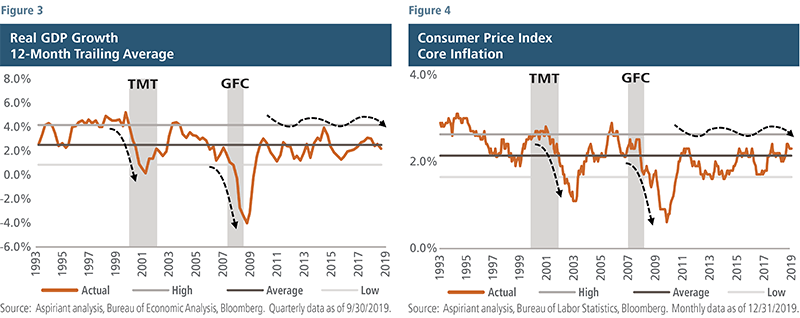

Figure 3 doesn’t seem to indicate that economic growth is overheating. Likewise, Figure 4 doesn’t suggest that inflation is on the rise. To the contrary, both indicators appear stable despite some mild upward drift in inflation and about an equally soft decline in economic growth; circumstances that generally prevail across the economies in most major countries. Given this, we don’t expect the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central bankers to take actions, such as raising interest rates, to preempt inflation and disturb the pace of economic activity. On the other hand, we believe these same monetary authorities lack sufficient policy flexibility, with interest rates currently at or near zero, to unilaterally arrest a material sag in economic conditions and prolong the business cycle.

Obscured pothole: Business-led downturn

Nevertheless, plenty of other triggering events can occur, including liquidity crunches, fiscal tightenings (e.g., reduced spending and/or higher taxes), health pandemics, trade wars, currency wars and military conflict.

Any combination of those catalysts could understandably cause business leaders, as well as households, to pull back on spending and investment. And similar to consumer spending habits, profit protection at one company causes profit vulnerability at another. As the impacted company seeks to protect its own bottom line, it too might cut back on spending, investment or employment. The spiraling continues across companies, resulting in a business-led pullback affecting economic growth (income earners) and financial markets (asset owners).

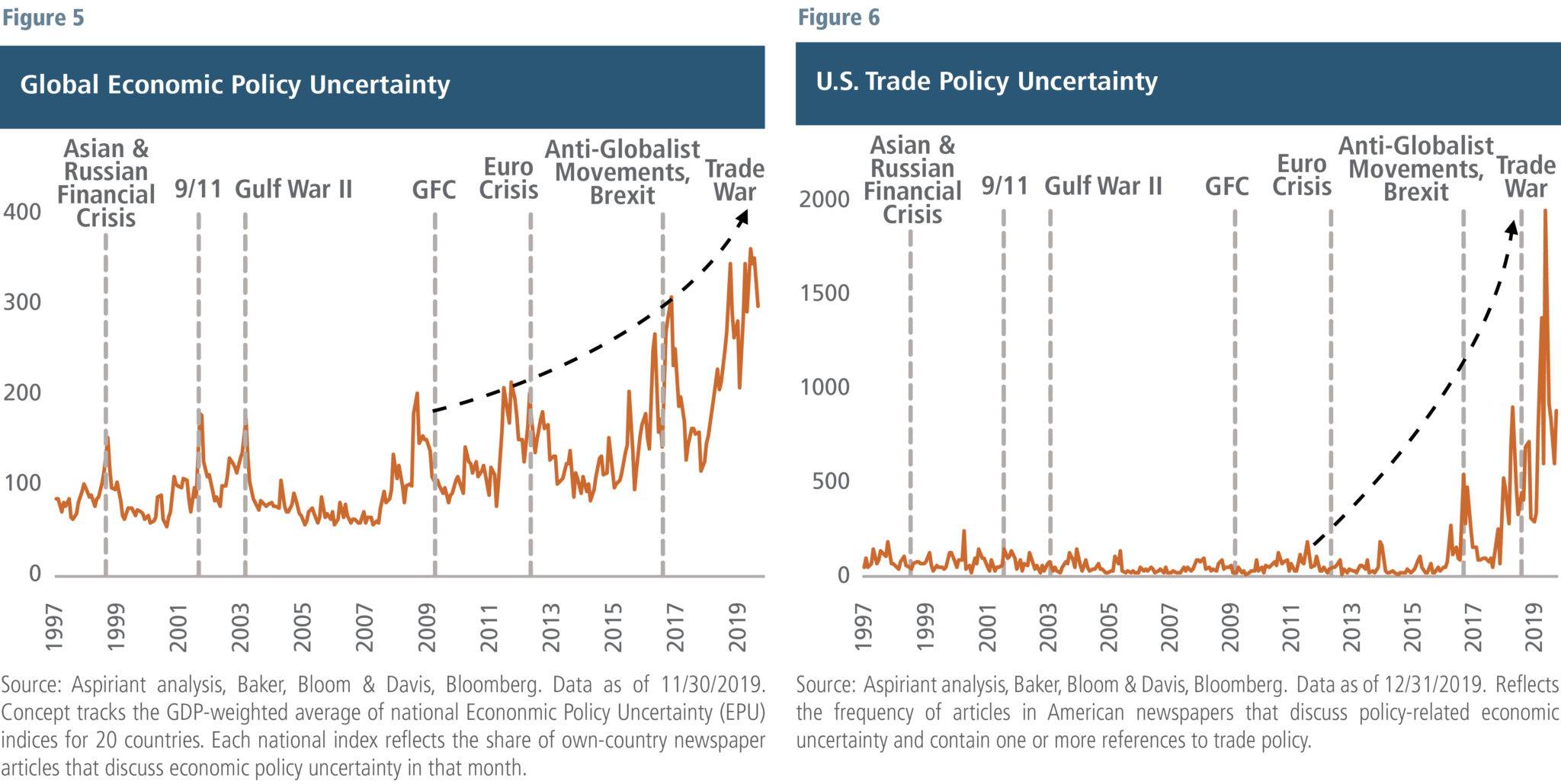

Figures 5 and 6, depicting uncertainty related to global economies and U.S. trade policy, present reasons for business leaders to be concerned about future economic stability.

Current levels of economic and trade policy uncertainty are at their highest levels over the past 20 years. And, historically, an increase in uncertainty has preceded a decline in economic growth and employment in the months ahead.

Unsurprisingly, a recent survey of global business leaders7 found that the risk of an economic slowdown potentially triggered by global trade uncertainty was among the respondents’ top concerns. Another leading concern was their company’s ability to attract and retain talented employees, which could lead to increasing wage pressures. Either of these occurrences — economic slowdown or wage inflation — would put downward pressure on corporate profits and price-to-earnings multiples (along with other valuation metrics), and likely prompt a decline in asset pricing.

CEOs losing confidence

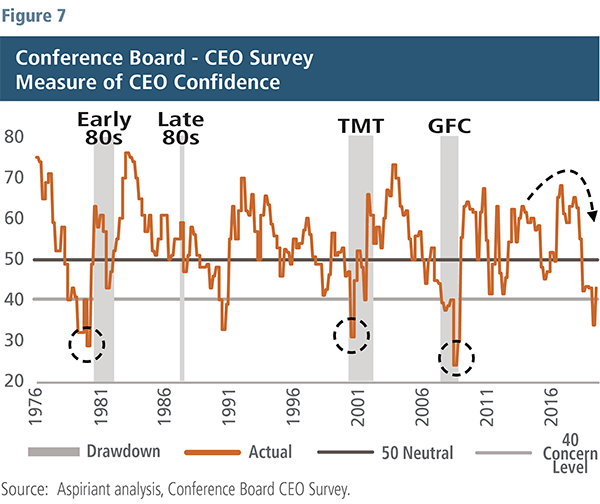

Given that the level of uncertainty is on the rise both at home and abroad, it’s no wonder CEOs are beginning to lose confidence. The survey index in Figure 7 measures the prevailing level of confidence across CEOs. A reading of more than 50 points reflects more positive outlooks, while a reading of less than 50 reflects more negative outlooks.

Since 1976, the index fell to a level of 40 or less on four different occasions. In three of those cases, the S&P experienced significant drawdowns: early 1980s (-16%), Technology Media Telecommunications pullback (-46%) and the Global Financial Crisis (-57%). During the third quarter of 2019, the index once again breached that level, providing another indication that downside risks are looming. With that said, the index rebounded a bit during the fourth quarter, indicating some relief related to ongoing trade and tariff discussions. Nevertheless, it seems clear CEOs are concerned about global growth prospects, creating apprehension with respect to spending and investment as we enter 2020.

According to the Conference Board’s CEO Confidence Survey, approximately 50% of CEOs surveyed expect flat-to-declining selling prices in 2020. Forty percent expect modest increases ranging up to 4%, while just 10% expect price increases in excess of 4%. Taken together, CEOs are expecting roughly flat year-over-year price changes. At the same time, after years of stubbornly low wage growth, workers are expected to earn about 3.6% more in 2020 versus 2019. Assuming these expectations hold, business leaders will be forced to either accept lower profit margins or make spending cuts elsewhere, which again could negatively impact equities.

Tapping the brakes?

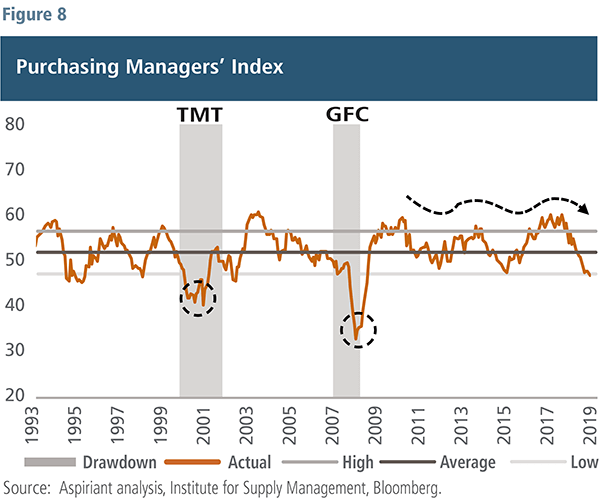

The Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) shown in Figure 8 is considered one of the most reliable leading indicators for assessing the direction of economic activity in the U.S. Based on a monthly survey of supply chain managers across 19 industries, the index serves as a proxy for the country’s overall level of economic stability, expansion or contraction. Measures above 50 are a mark of economic growth while indications below 50 signal economic deterioration.

Since August 2018, the PMI has been on a steady decline. Following the breach of the neutral barometer of 50 in August 2019, the index has flashed a warning sign of recessionary activity. Disaggregating the data reveals the overall PMI is currently affected by a more pronounced slowdown in manufacturing versus services. Regardless, the trend is worrisome and bears close monitoring, particularly now that the trade conflict with China has been (ostensibly) settled.

Moreover, if the PMI remains at or near existing levels in the months ahead, then the data cannot be easily dismissed as “noise,” and business leaders may become more aggressive in their reaction to the state of economic affairs.

Indeed, executives representing a cross-section of industrial suppliers — including Caterpillar, Honeywell, CSX, DuPont, W.W. Grainger and 3M — all recently made downward revisions to their forward growth guidance.

Avoiding a major collision

Ask yourself: Is the fact that a driver hasn’t had an accident in the past 10 years evidence that they would likely drive safely going forward? Isn’t it possible that they simply got lucky?

Similarly, haven’t investors benefited from an extraordinary run of good fortune? Artificially low (and in some cases negative) interest rates, massive purchases of financial assets, enormous late-cycle fiscal stimulus, an utter disregard of budget deficits by elected officials, and rising industry concentration have all upended patterns we have seen for much of the past 50 years.

From the highest level, the things we worry about going “wrong” is a reversal in the things that have gone “right” for investors over the past several years. While many of the favorable dynamics underpinning the market advance since 2009 will be slow to change or unwind, it seems to us the probability of upside surprises is less likely and that investor luck will turn, as it always does.

As much as we would like to, we can’t predict with certainty when these circumstances will retreat. But we can design well-diversified portfolios that we expect to perform reasonably well, regardless of the environment. We remain committed to that pursuit.

1The global balanced portfolio achieved an annualized return of at least 6% in 52.5% of the 300 seven-year rolling monthly periods since 12/31/1994. Aspiriant expects its Moderate Portfolio, which is benchmarked against a global balanced portfolio, to also achieve an annualized return objective of CPI +2% (or roughly 6% today).

2For a broader discussion on Big Tech and growth stocks, please see our Third Quarter 2019 Insight, published in October 2019.

3For a broader discussion on how to achieve an adequate return objective in the midst of a low return environment, please see our First Quarter 2017 Insight, published in April 2017.

4Source: Bloomberg, “Fidelity to Baby Boomers: Lay Off the Stocks,” November 13, 2019. According to the article, Fidelity recommends 70% in equities for clients at least 10 years away from retirement.

5Baby boomers are considered the generation of Americans born between 1944 and 1964. The cohort currently consists of 72 million people, ranging in age from 55 to 75 years old.

6For a broader discussion of business cycles and market cycles, please read The Market Cycle and the Business Cycle: A Layman’s Guide, written by our colleague Ryan Nelson, director in wealth management, published in January 2020.

7Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers’ 23rd Annual Global CEO Survey: Navigating the rising tide of uncertainty.

Important Disclosures

Aspiriant is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which does not suggest a certain level of skill and training. Additional information regarding Aspiriant and its advisory practices can be obtained via the following link: https://aspiriant.com.

Investing in securities involves the risk of a partial or total loss of investment that an investor should be prepared to bear.

Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.

The views and opinion expressed herein are those of Aspiriant’s portfolio management team as of the date of this article and may change at any time without prior notification. Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. All investments can lose value. Indices are unmanaged and you cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of any index may be materially different than that of a model. The charts and illustrations shown are for information purposes only. All information contained herein was sourced from independent third-party sources we believe are reliable, but the accuracy of such information is not guaranteed by Aspirant. Any statistical information in this article was obtained from publicly available market data (such as but not limited to data published by Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates), internal research and regulatory filings.Equities. The S&P 500 is a market-capitalization weighted index that includes the 500 most widely held companies chosen with respect to market size, liquidity and industry. The MSCI ACWI Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of developed and emerging markets.Fixed Income. The Barclays Municipal Bond Index is a rules-based, market-value-weighted index engineered for the long-term tax-exempt bond market. The index has four main sectors: general obligation bonds, revenue bonds, insured bonds and pre-refunded bonds.

Talk to us

Talk to us