Successful investing requires discipline

Over the past several years, U.S. equities have been on an absolute tear — generating an annualized return of 13% to 14%, depending on the reference index. But, like all good things, the ride must come to an end. We believe U.S. equities have run well beyond their fair value.

At today’s prices, our forecasts suggest the S&P 500 is poised to generate just 1.5% annualized over the next seven years.1 While we may be one of the few firms broadcasting this warning, we are not alone. To the contrary, we are in good company with some of the most well-respected firms in the investment management industry. An equally weighted forecast of three of these firms predicts an annualized return of 0.0% (nil) for the S&P 500 over the next seven to 10 years.2 So, by comparison, we are a bit optimistic.

Luckily, it’s not all bad news. Going forward, we see some relatively attractive opportunities, including defensive equities, defensive strategies and emerging equities. For example, our forecast for broad emerging market equity returns over the next seven years is 3.6%, annualized. The composite forecast of the same three investment firms mentioned above pegs emerging markets at 5.5% annualized. So, opportunities exist, but to take advantage of them, successful investors must have the framework, discipline and ability to perform the requisite analysis. Otherwise, you’re likely to become susceptible to emotion and speculation.

Fear of missing out

There’s a concept used in social media circles called the fear of missing out, which is often referred to by its acronym, “FOMO.” It can be thought of as a fear of being left behind or missing out on an opportunity.

FO·MO

/fōmō/

pent-up anxiety that you are not benefiting from what appears to be an attractive investment opportunity

The concept can be adapted to investing,3 as we have defined above. For example, an investor suffering from this anxiety may rotate into, or hesitate to reduce, exposure to U.S. equities, fearing they will miss out on more record highs. Those investors often cite qualitative reasons to justify their decision such as increasing growth, high profitability, low unemployment, tax reduction and regulatory reform. However, they never put pencil to paper. They invest impulsively with passion rather than prudence, expect the future to mirror the recent past, and ignore any number of cautionary signals. And, in the end, they will likely suffer (as they often have in the past) from severe pullbacks — during which they become paralyzed with fear. Investing through all stages of a market cycle requires critical thinking and the discipline to move away from popular convention.

Think you’re too smart to succumb to FOMO? Think it’s a relatively new phenomenon? Well, it happened to Sir Isaac Newton more than 200 years ago.

Neither apples nor valuations can defy gravity

Sir Isaac Newton (1643 ‒ 1727) was an English mathematician, astronomer and physicist who is recognized as one of the most accomplished scientists of all time. Throughout his career, Newton advanced our collective understanding in a wide range of areas. For example, his book, “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,”4 is considered one of the most influential books in physics. In reflecting on Netwon’s distinctive contributions, economist John Maynard Keynes once remarked:

Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind that looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than 10,000 years ago.

Newton is most commonly credited for developing his theory of gravity after watching an apple fall in an orchard. Given that perceptiveness, it is ironic that he was unable to anticipate that gravitational force also applied to stock valuations.

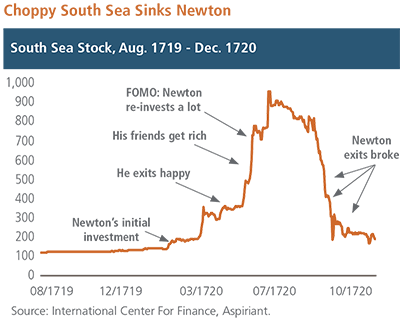

The South Sea Company was founded in 1711 as a public-private partnership to consolidate and reduce England’s national debt5 in exchange for the company’s exclusive right to trade with South America. Expectations ran wild for trade between the two regions, causing the company’s stock to skyrocket during late-1719 to mid-1720 (see chart below).

As shown, Newton first invested a modest amount of capital in the South Sea Company when it was trading around £170 per share. At the time, he was 77 years old and had clearly learned a lot throughout the course of his lifetime. As speculation in the company spread and the stock price moved higher, Newton sold, earning a profit of £7,000 in less than 12 months. He should have been happy. However, the stock continued to climb over the next few months. Fearing that he sold too early and was missing out on further gains, Newton decided to make a large, concentrated bet in the stock at approximately £720 per share.

Around the same time, news spread that actual trade with South America was much more limited than originally anticipated. As a result, the company failed to generate sufficient revenue to service its debt. In addition to lower trade expectations, the South Sea Company became embroiled in allegations of insider trading, fraud and deceit. The market reacted swiftly.

After peaking around £1000 per share, the stock tumbled, with Newton selling at ever-decreasing prices ranging from approximately £500 to £200 per share. Newton ended up losing £20,000, which represented the bulk of his net worth. He was devastated, but not alone. The widespread calamity was felt across England and Europe, destroying considerable wealth and throwing the economic region into recession. Over time, the event became known as the South Sea Bubble. As the bubble grew Newton coined one of his most famous quotes:

I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.

Checklist: Are you an investor or speculator?

We, at Aspiriant, consider ourselves to be investors. That’s not because we have anything against speculators, we just don’t believe anyone has consistent skill when it comes to market timing. Below, we have assembled an admittedly unscientific checklist to help identify speculators and investors.

| Checklist | Speculator | Investor |

|---|---|---|

| Your time horizon is: | short | long |

| You check your portfolio value: | frequently, perhaps daily | seldomly, perhaps quarterly |

| You compare investing to: | gambling | science |

| You invest: | impulsively/passionately | prudently/dispassionately |

| Willingness to hold non-consensus point of view: |

low | high |

| You most fear underperforming during: | up markets | down markets |

| Your use of margin/debt: | increases in extended markets | decreases in extended markets |

| You tend to modify your portfolio allocations by: | increasing winners, selling losers | increasing losers, selling winners |

| At cocktail parties you: | tout your winners, but rarely your losers | share lessons learned, and want to learn from others |

| You believe markets are: | always efficient, but you still believe that you can outperform in all environments | generally, but not always, efficient and that knowledge and discipline enables you to outperform in certain environments |

| Your portfolio is: | concentrated, consisting primarily of U.S. equities, which you believe always win | globally diversified, because you understand that no asset class is ordained to win in all environments |

| Your investing heroes are: | possibly no one; and you probably wouldn’t recognize half of the names on our heroes list | a few academics, but primarily investment professionals with time-tested track records of attractive risk-adjusted returns |

Although we present the checklist in tabular format, it is more appropriate to think about speculating and investing along a continuum. For example, if you are currently buying U.S. equities because you’re hoping they’ll generate 12% to 15% returns again next year, then you’re a speculator. If, however, you’re holding U.S. equities for the long haul — understanding that valuations are high and annualized returns will average about 0% to 3% over the next several years — then you’re an investor.

Footnotes:

1Based on our Capital Market Expectations as of September 30, 2017.

2Equally weighted composite forecast of three of the most reputable investment management firms as of September 30, 2017. For confidentiality purposes, Aspiriant only discloses the identity of the firms to its clients.

3When adapted to investing, the concept is similar to regret aversion in behavioral finance.

4The book was originally titled, “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.”

5Much of England’s debt at the time resulted from financing its war with Spain, which controlled South America. It was envisioned that trading between England and South America would begin following the end of the war.

Important disclosures:

Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. All investments can lose value. Indices are unmanaged and it is impossible to invest directly in an index. The volatility of any index may be materially different than that of a model.

Talk to us

Talk to us