Part II: Bridging the gap

In Part I of our First Quarter Insight, we discussed the growing economic hole impeding our path forward. The massive shortfall, which we currently estimate between $50 trillion and $60 trillion, resides on the collective balance sheets of our country’s inhabitants. Given its sheer size, there’s no point spending time on solutions offering billions of dollars when the problem is in the tens of trillions.

So in this Part II, we focus our attention on a handful of sufficiently scalable options to grow, tax, spend, borrow or inflate our problems away. While we discuss them individually, we suspect a combination of choices will be pursued. Since each approach comes with trade-offs, most of us will bear a portion of the overall costs. However, some groups will no doubt shoulder a disproportionately heavier burden to get us to the other side.

Can’t we just grow out of our problems?

In 2019, the U.S. accounted for 24% of the world’s total gross domestic product (GDP), generating $21.5 trillion in economic output. So, it’s worthwhile to consider whether we can accelerate growth and repay our debts over time. Unfortunately, we don’t believe that’s realistic, at least not anytime soon.

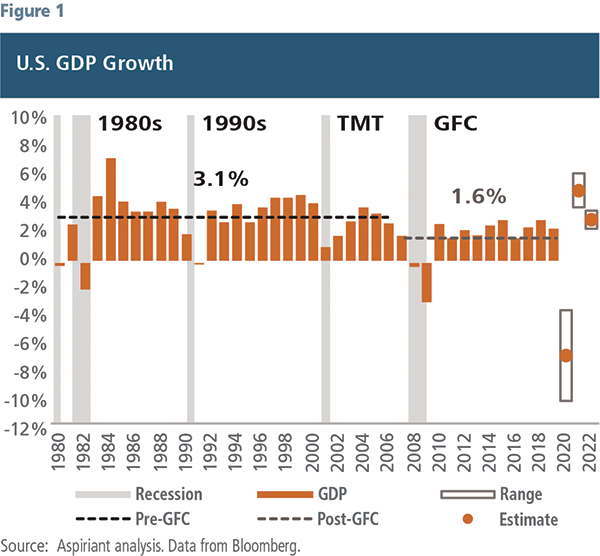

Figure 1 plots U.S. real GDP growth over the past four decades. Prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the United States experienced average annual economic growth, adjusted for inflation, of about 3.1%. While not explosive, that pace supported a gradually rising standard of living, represented by an increasing amount of goods and services produced and consumed across the country.

But then, the GFC caused widespread devastation. The impact was exacerbated as two important growth factors — population and productivity — had been in steady decline for years. As a result, in not one year over the past 12 have we achieved the average level attained in prior decades. In fact, average economic growth has been roughly half of the previous average at just 1.6% annualized.

This step down has made it very difficult for the average American to reclaim the financial stability achieved pre-GFC. For example, median annual household income, adjusted for inflation, increased by just $2,900 in the nearly 12 years since 2007.1 Over the same period, the costs of essential services like housing, health care, childcare and education ballooned, exposing the masses to greater vulnerability during downturns.2

The current crisis dealt an even bigger blow. The bars outlined in gray represent our estimated range of GDP growth in 2020, 2021 and 2022. The orange dots represent the midpoints of those ranges. While we’re not trying to be overly precise, the approach indicates the economy will contract by 6.8% this year, marking the second largest annual decline since the Great Depression.

Although we expect the economy to recover in 2021 and 2022, the average over the next three years (not shown), is likely to be relatively flat at less than 1% annualized. As a result, we don’t see a viable way to grow out of our problems in the near-term. So, we’re going to have to deal with them another way.

Why don’t we just increase taxes?

Given the currently fragile economic environment, it may not be wise to increase tax rates. Nevertheless, the nation’s total annual tax revenue is sizable at $3.5 trillion, making the topic worthy of discussion, including which taxes might be reassessed.

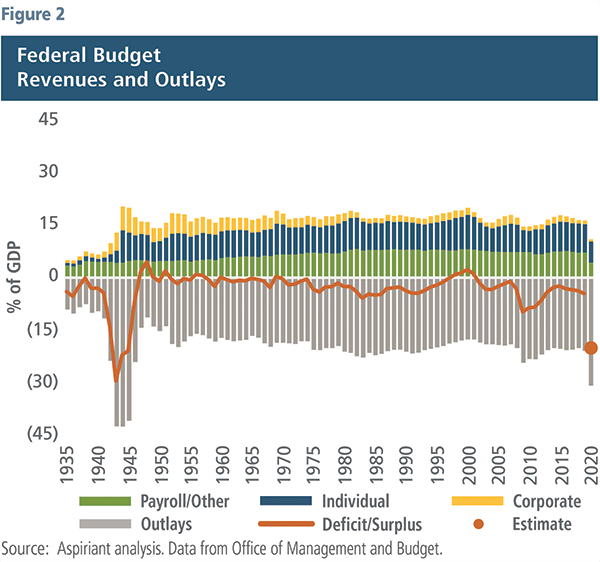

Figure 2 displays the country’s national deficit/surplus (orange line), tax revenues (colored bars) and spending outlays (gray bars). The data points are presented on a percentage-of-GDP basis to make them more comparable over time. As shown, notwithstanding the politicization of deficit-spending, over much of the past 85 years, we have generally run minor deficits with occasional surpluses. One exception was the early 1940s as President Franklin Roosevelt mobilized the country and oversaw vast spending to support the war effort, and in doing so, finally brushed aside the enduring remnants of the Great Depression.

From 2008 through 2012, the country incurred annual deficits of approximately 10% to help curb the impact of the GFC. The economic rout caused by the coronavirus is set to make that level pale in comparison. Although rough estimates, we wouldn’t be surprised to see this year’s deficit reach $3.7 trillion, or approximately 20% of estimated GDP (orange dot), triggered by the massive increase in outlays and simultaneous collapse in revenues.

The chart breaks down the revenue streams into payroll taxes, individual income taxes and corporate taxes. Given the catastrophic losses currently afflicting employers and employees, we’re expecting significant declines in each category in 2020. Nevertheless, increasing taxes, especially those targeting certain groups, will likely be part of any overall comprehensive solution.

For a variety of reasons, we doubt that individual or payroll taxes will be targeted. First, those taxes have already provided the lion’s share of the country’s budget over the years. Second, such increases would likely apply to higher income earners, many of whom are already paying more than 50% in federal and state taxes. Third, even some of the most progressive tax increases being proposed on high-earners and the ultra-wealthy would do little to generate meaningful increases in federal receipts.

So, we suspect corporations will be the most likely target for tax increases, which could offer greater impact and garner political support. Over the past several decades, corporate taxes have dwindled, significantly reducing their contribution to our national budget. Although the trend created a powerful boost for businesses and shareholders, it also led to an ever-widening gap between those with more and less wealth. The current environment might prompt a reevaluation of the soundness of these outcomes.

Will consumers increase spending?

The American consumer accounts for 70% of U.S. GDP and 17% of global GDP. So, it’s natural to look to them as a potential catalyst driving the economy forward. Unfortunately, as we discussed in our Second Quarter 2018 Insight, recent surveys3 have underscored consumer vulnerability coming into the current crisis. For example, nearly 80% of workers self-identify as living paycheck-to-paycheck. Moreover, 40% of households earn less than $40,000 per year, with 25% earning less than $25,000.

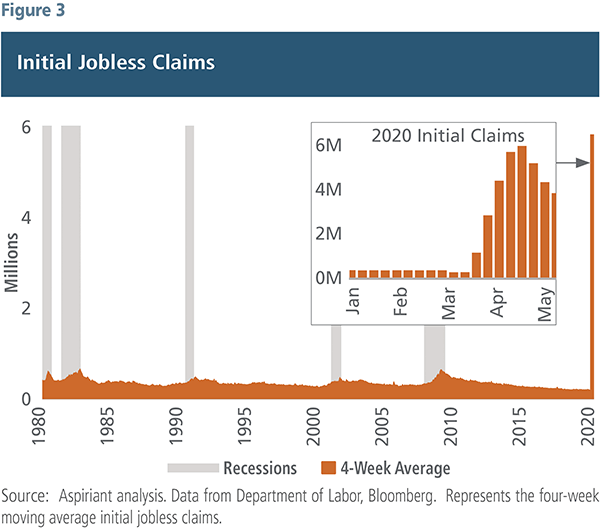

Regardless, the perennially stable job market gave many Americans little reason to believe their financial stability could be jeopardized. Figure 3 shows jobless claims across the country since 1980. As shown, the four-week average (which dampens weekly distortions) has closely fluctuated around 400,000. In fact, each time the average exceeded 550,000 claims, a recession occurred, as indicated by the gray shaded areas.

But then the pandemic hit and a tsunami of job losses began building as state and local governments ordered non-essential businesses to close and individuals to shelter at home. As a result, jobless claims spiked to levels never before seen. Indeed, beginning with the week ended March 27, the average jumped to 2.7 million, climbing even higher over the next few weeks (see chart inset). Thankfully, the rate of job losses seems to have cooled in recent weeks, although the aggregate number of claims remains well above historical norms.

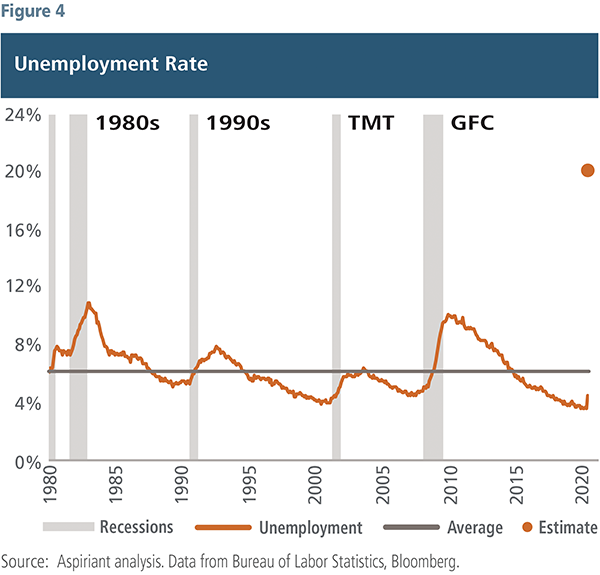

As shown in Figure 4, that wave of job losses led to a staggering increase in the nation’s overall unemployment rate. For historical context, since 1980 the country’s average unemployment rate has been 6.0%, which is generally considered “full employment.” Interestingly, while some believe low levels of unemployment indicate an economy’s strength, an overly tight labor market portends bad times ahead, as indicated by the gray shaded recessions. We have warned about the perils of misinterpreting employment data, including in Part I of our Second Quarter 2019 Insight.

Since official unemployment tends to lag the actual level by a few weeks, we have included a rough estimate (orange dot) based on the pre-crisis unemployment rate adjusted for the surge in initial jobless claims, among other factors.

Clearly, if consumers were vulnerable before the global pandemic, they are most certainly in peril now. This dramatic reduction in incomes leads us to believe that consumption will be suppressed for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, we believe the experience, like that of the GFC, will cause people to save more, setting aside more of their disposable income for unplanned emergencies and retirement. Therefore, we think it’s highly unlikely that elevated consumption alone will take us to the other side of the economic hole.

Will households borrow?

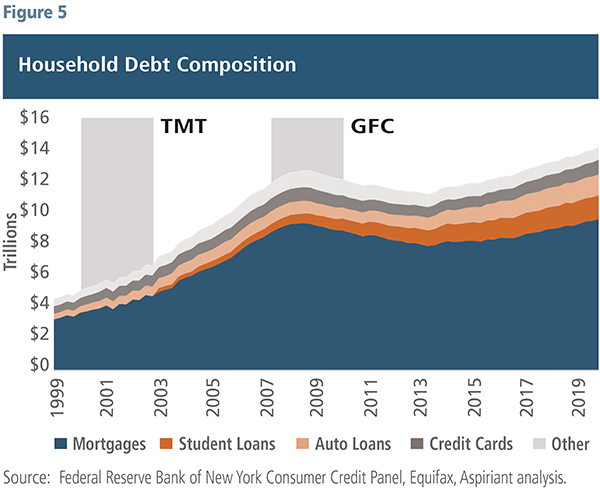

While job and income losses weaken consumption, purchases of goods and services are also driven by the willingness and ability of households to borrow. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, household debt in the fourth quarter of 2019 stood at an all-time high of $14.1 trillion, marking the 22nd consecutive quarter of credit creation, as shown in Figure 5.

Remarkably, even after two decades of economic expansion, many Americans have fallen short on cash, increasingly relying on debt to fund their lifestyles. Pre-coronavirus surveys revealed 50% of U.S. households had less than $12,000 saved, 30% had less than $1,000 and 25% had no savings or pension.

In order to make ends meet, we suspect many already have, or soon will, further deplete their savings by taking advantage of certain provisions under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. By increasing distribution and borrowing limits, as well as eliminating or delaying penalties and taxes, the act made it easier for people to use their retirement accounts (401(k), 403(b), IRA, etc.) to replace lost income. While such actions may help stabilize the economy in the short run, we worry they could lead to significant long-term consequences by further eroding the financial security of millions of people.

It’s common for household debt to increase during economic expansions and then become unsustainable in contractions. In fact, many households extract credit from their homes using cash-out refinancing, which increases financial risk by reducing a home’s equity cushion. Tapping a home’s equity would not be concerning if the proceeds were used to repay higher interest debt. However, it doesn’t appear that other debts have been repaid. To the contrary, increases have occurred across the board with student loans, auto loans, credit card balances and mortgages climbing over the past 10 years.

So, it’s no surprise that payment delinquencies have begun to tick upward, likely indicating a reluctance or inability for many households to further increase credit. Traditionally, late or no payments on any form of loan and an interruption in income were large red flags or disqualifiers in extending credit. The CARES Act attempts to address this possibility and limit the credit score implications of job and income losses from the pandemic. However, access to credit will be constrained as many financial institutions tighten lending standards, withdraw certain higher risk products from the market (e.g., lower documentation loans, home equity lines of credit) and raise the cost of borrowing to account for more uncertain payment outcomes.

What if we inflate the debt away?

Another way to handle the country’s massive debt load is for the U.S. Federal Reserve to inflate our liabilities away by printing dollars and repaying the debt with the greater amount of currency in circulation. Supported by Modern Monetary Theory,4 the notion may first seem appealing, but we believe it is incredibly complicated.

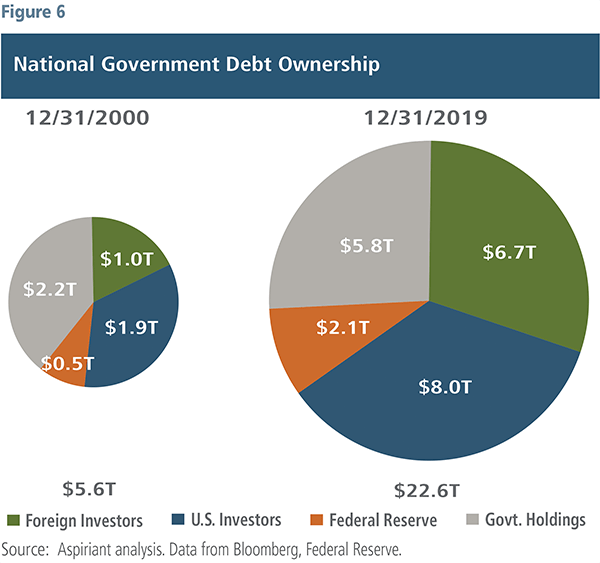

As shown in Figure 6, our headline national debt has more than quadrupled over the past 19 years, from $5.6 trillion to $22.6 trillion. It’s important to recognize that one person’s debt is another person’s asset. So, the pie charts show the asset holders (investors) who currently own our country’s debt obligations.

Coordinated action by the U.S. government and Federal Reserve to fund growing budget deficits by printing more money is a distinct and likely possibility, particularly given the reserve status of the dollar and the global appetite for dollars. However, doing so can lead to mounting inflationary pressures and a reduction in the real value of all outstanding debts and assets. While this result would benefit debtors like the U.S., creditors or investors in dollar-denominated Treasury securities would be displeased. Our trading partners (foreign investors) whose goods and services are often settled in dollars (with those dollars getting recycled into U.S. Treasurys and other dollar-based financial assets), as well as our own businesses and citizens (U.S. investors) who rely on Treasurys for investment safety and income stability, would be among the parties most impacted.

To entice those groups to invest in the future, the Fed might need to raise interest rates to offset the erosion in real purchasing power brought on by a rising inflationary environment. Otherwise, investors may logically choose to hold other securities — such as foreign currencies, cryptocurrencies, gold, etc. — perceived to offer a better store of value. Unfortunately, higher interest rates would likely dampen economic activity as consumers, businesses and governments reduce spending to service their growing debt service obligations.

Therefore, while printing money may sound like a quick fix, we believe it would have wide-sweeping implications, ushering in yet unknown risks for the overall health of the country.

Prepared for crashing waves

We applaud Washington and the Fed for acting swiftly to contain the economic downturn triggered by the coronavirus. Their collective actions provided substantial economic relief to businesses, households and financial markets. However, in order to achieve that result, they needed to pile on trillions of dollars to an already towering debt stack. Managing through those obligations will take time, and we expect the economy to experience lingering effects for years to come.

Given the country’s weakened state, we worry that any second waves — health, economic or investment — could further frustrate our capacity to whittle away at the problems.

Across emerging markets, some countries, including China, South Korea and Taiwan, appear well-equipped to continue battling the combined health and economic challenges. Indeed, they have handled the crisis better than several developed countries, including the United States. Other countries appear more vulnerable. We worry that some of these countries will fail to properly cope with the problems, which could lead to a resurgence in the health crisis as global travel resumes.

The plausible range of outcomes going forward is wider than at just about any other time in our careers. At one end of the spectrum, growth and employment could quickly recover with low interest rates and stable inflation. At the other end of the spectrum, a second wave could lead to a prolonged and difficult rebound, as well as higher debts, more money printing and a greater risk of ascending inflation.

Prevailing equity valuations, especially U.S. stocks, exclusively embed the expectation that the best-case scenario will occur and we’ll return to pre-pandemic economic activity in the next few quarters. Given the broad spectrum of possible endpoints, we do not believe now is the time to take undue risk. Holding well-balanced, globally diversified portfolios that respond to a range of good and bad scenarios seems the most sensible way to handle the uncertainty before us.

1Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Sentier Research Household Income Trends.

2Please see our Fourth Quarter 2018 Insight for a broader discussion about the health of the American consumer.

3Sources: Career Builder Survey, United Way, MagnifyMoney, Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households, U.S. Federal Reserve Board, Northwestern Mutual’s 2018 Planning & Progress Study. Other surveys referenced include those conducted by SmartAsset and GOBankingRates, each of which reached findings.

4Please see our Second Quarter 2019 Insight-Part II for a description of Modern Monetary Theory.

Important Disclosures

Aspiriant is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which does not suggest a certain level of skill and training. Additional information regarding Aspiriant and its advisory practices can be obtained via the following link: https://aspiriant.com.

Investing in securities involves the risk of a partial or total loss of investment that an investor should be prepared to bear.

Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.

The views and opinion expressed herein are those of Aspiriant’s portfolio management team as of the date of this article and may change at any time without prior notification. Any information provided herein does not constitute investment or tax advice and should not be construed as a promotion of advisory services.

Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. All investments can lose value. Indices are unmanaged and you cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of any index may be materially different than that of a model. The charts and illustrations shown are for information purposes only. All information contained herein was sourced from independent third-party sources we believe are reliable, but the accuracy of such information is not guaranteed by Aspirant. Any statistical information in this article was obtained from publicly available market data (such as but not limited to data published by Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates), internal research and regulatory filings.

Talk to us

Talk to us